Resilience in Critical Care

- Home

- Resilience

- Resilience in Critical Care

Managing Exposure: A Grounded Theory of Burnout and Resilience in Critical Care Nurses

This summary explains my research study for my Master’s thesis, where I set out to learn how critical care nurses become resilient. You can read the entire thesis here, watch a short YouTube video here, or a detailed YouTube video summary here. There is also a Resilience Plan handout, an evidence-based tool to support self-reflection. This handout has also been adapted into a staff booklet.

Burnout was identified in nursing in 1978[1], and continues to be problematic in the profession[2]. There are many factors that make critical care settings challenging places to work, and burnout among critical care nurses remains high[3]. However, we also know that resilience is an important factor for critical care nurses. Resilience can be defined as “the ability of an individual to adjust to adversity, maintain equilibrium, retain some sense of control over their environment, and continue to move on in a positive manner.”[4] Essentially, resilience is the ability to address something difficult in one’s life in a healthy, positive way. Resilience is important for a lot of professionals, including teachers[5] and soldiers[6], and it was suspected that resilience would be important for nurses as well.

Resilience has been widely studied, in a variety of contexts. However, many of these studies have focused on personality traits associated with resilience, or prevalence rates of resilience or burnout. In this study, I explored how resilience actually happens; that is, how nurses go from experiencing adversity to becoming burnt out or resilient. By explaining how nurses become resilient, we can support nurses by making the process of resilience more visible and easier to manifest. This research is important because we know that resilient nurses call in sick less frequently[7], and can provide safer care to patients and their families. There are nursing and economic benefits to having a resilient nursing workforce.

I spoke with 11 nurses in critical care settings, for up to 90 minutes. We discussed a variety of topics about their experiences at work, their efforts to cope with challenges, and their beliefs about the nursing profession. I combined all of this information to create a framework showing how nurses become resilient. I hoped that if I could illustrate how nurses become resilient, we could make it easier for nurses to follow this process.

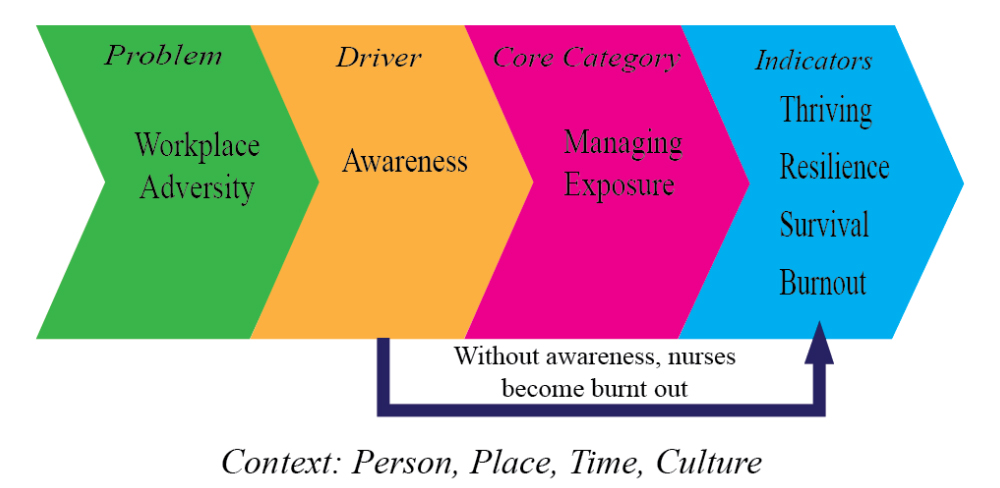

So how do nurses become resilient? By Managing Exposure. This model explains how nurses become burnt out or resilient, which opens the door to strategic interventions.

It is important to note that this model is presented as being linear and one directional for ease of explanation. In reality, these processes are dynamic and fluid.

Resilience begins when nurses face adversity. There are many forms that adversity can take; for the purposes of this study, the focus was on adversity that is found in the workplace. Nurses reported several levels of adversity that they encounter every day at work. These included broad, societal influences, such as a lack of respect for nursing. Nurses reported that many people (including patients, families, and nurses’ family members) did not understand or appreciate the role of nurses in critical care. This lack of understanding translated to disrespectful treatment and a lack of support.

Adversity was also found in the culture of the unit, practical concerns, the nature of critical care nursing, and interpersonal conflicts. Nurses described difficulty caring for patients when they plan of care was not what a nurse thought would be best for the patient. Nurses also reported that an inability to access vacation time from work made it difficult for them to address burnout.

There are lots of factors that constituted workplace adversity for nurses. Rather than see these as a list of problems, it is important to recognize that each point is a place where intervention can make a difference. There are concrete opportunities in the workplace to decrease the amount of adversity faced by nurses. While it is impossible to have an adversity-free workplace, there are many ways to decrease adversity and make nursing more manageable.

The factor that moves this model forward is awareness. When nurses had awareness about how they were being affected by workplace adversity, they could make choices to manage their exposure to this adversity. Awareness created the opportunity for nurses to take action.

In order to have awareness, nurses required a disclosure of information that was relevant to their work. They could perceive and understand this information, reflect on it, and consider the outcomes of different courses of action. Based on these potential outcomes, a nurse would choose how to respond.

Awareness is important because it is how nurses understand their experiences and make decisions. If nurses did not have awareness, they would become burnt out.

The most important part of this model is Managing Exposure. This is the actions that nurses take to address workplace adversity.

When nurses work in infectious environments, they put on protective equipment, limit their time in sensitive areas, remove the equipment when they leave the area, and clean their hands as they move away. Nurses can use these same strategies psychologically as well, in order to manage their exposure to workplace adversity.

These actions fell broadly into 4 categories:

Strategies that nurses used to emotionally protect themselves from adversity, and offload when they were overwhelmed. This included developing a protective shell against emotional concerns, and delegating tasks to colleagues.

How nurses made meaning from their experiences in critical care. The most common form of processing was talking about challenges at work, especially during change-of-shift report. This time was preferred because it was private, normal, and nurses could talk to someone who shared their experiences.

Restorative processes that nurses can use to be rejuvenated after difficult experiences. These included developing supportive relationships at work, and outside of work. Nurses also managed exposure by engaging in meaningful activities that were either physical, such as yoga, or creative, such as knitting.

The need for nurses to be physically away from the patient bedside. This included short periods of time, such as breaks or a few minutes to recover after a crisis. Nurses also periodically needed longer breaks, such as granted vacation. Ultimately, many nurses recognized that it was difficult for them to manage their exposure to adversity in critical care, and would begin planning to leave the unit years in advance, in anticipation of their own burnout.

Nurses told me that they were the most resilient when they could easily use these strategies, with the support of their colleagues, families and organizations. Nurses who used a variety of these strategies told me that they felt more resilient than nurses who only used one or two strategies.

There are a variety of ways that nurses experienced the process of Managing Exposure. Nurses reported they were thriving when they loved their work, and felt passionate, energized, and fully engaged. Nurses achieved resilience when they were able to face difficulties in the workplace, and feel good about the nursing care they could provide. Nurses described themselves at a survival level when they said they struggled at work, but they were trying to retain their compassionate approach to patient care. Finally, nurses reported burnout when they saw patient care as a series of tasks rather than a caring act. They felt anxious before or after work, had difficulty separating their professional and personal lives, and felt like they did not have adequate time to recover between shifts.

It is likely that burnout can lead to post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but as PTSD is a psychiatric diagnosis, it was beyond the scope of this study to investigate it directly.

So what does it all mean?

The major finding of this study is that nurses who are burnt out and nurses who are resilient are coming from the same pathway. Just as dating can lead to breakups or marriages, the exposure to adversity can lead to burnout or resilience. Nurses who are burnt out are not bad people, or lacking in personal coping skills. They are having difficulty managing their exposure, which can occur because of personal challenges or systemic barriers. For example, previous studies have identified burnout as a source of increase sick calls7. My research adds another dimension to this: nurses are experiencing burnout and they are trying to manage (potentially by requesting vacation, or trying to seek out interpersonal support). If nurses are not able to manage, such as not being able to get vacation hours granted, or being overwhelmed at home and unable to spend time with support people, they resort to calling in sick because they see no other options. The findings of this study clearly demonstrate that resilience and burnout are not entirely determined by individual nurses. There are systemic factors that can overwhelm a nurse, in spite of good personal coping skills. Workplace adversity can have a toxic impact on nurses, and needs to be taken seriously.

The findings of this research study also demonstrate the power of intervention to foster nursing resilience. Nurses shared stories of managers, educators, and colleagues, who had supported them through teaching and advocacy. It is clear that nurses learn how to promote their own resilience, and can be positively impacted by the people and systems around them.

It is important that nurse leaders consider how to support nurses to manage their exposure, to promote safe, dignified healthcare delivery.

The empirical publication from this research is available here from the journal Intensive and Critical Care Nursing.

Jackson, J., Vandall-Walker, V., Vanderspank-Wright, B., Wishart, P., & Moore, S. (2018). Burnout and resilience in critical care nurses: A grounded theory of managing exposure. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2018.07.002

This research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Nurses Foundation, and Athabasca University. These resources developed from this study are freely available to reflect the public nature of the research funding. I wish to express my sincere gratitude to all donors, especially the late Lt. Colonel Harriet Sloan, who donated funds to the Canadian Nurses Foundation in support of one of my awards. She is a veteran of WWII, and has dedicated her life to nursing at home and abroad.

For more information, please see:

[1] Shubin, S., & Milnazic, K. (1978). Burnout: The professional hazard you face in nursing. Nursing, 8, 22-27. Retrieved from: http://journals.lww.com/

[2] Epp, K. (2012). Burnout in critical care nurses: A literature review. Dynamics, 23, 25-31. Retrieved from: http://www.caccn.ca/en/publications/dynamics/

[3] Khamisa, N., Peltzer, K., & Oldenburg, B. (2013). Burnout in relation to specific contributing factors and health outcomes among nurses: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10, 2214-2240. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10062214

[4] Jackson, D., Firtko, A., & Edenborough, M. (2007). Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 60, 1-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04412.x

[5] Taylor, J. L. (2013). The power of resilience: A theoretical model to empower, encourage and retain teachers. Qualitative Report, 18, 1-25. Retrieved from: http://web.b.ebscohost.com/

[6] Simmons, A., & Yoder, L. (2013). Military resilience: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 48, 17-25. doi:10.1111/nuf.12007

[7] Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Van Rhenen, W. (2009). How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 30, 893–917. doi: 10.1002/job.595