Nursing labour

- Home

- Nursing Work

- Nursing labour

How do nurses do their work? Part of my research looked at how other researchers have answered this question. I read over 100 articles, from 1950 to present. I found that nurse researchers have understood nursing work as different types of labour- which is explained on this page.

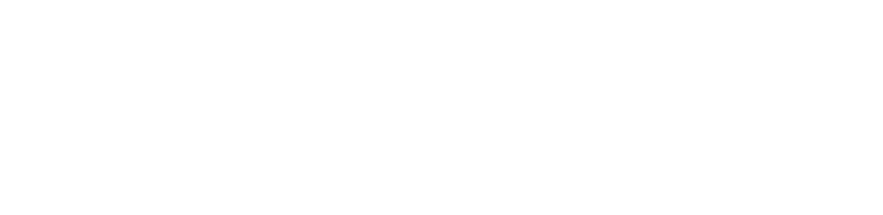

There are three main findings from this work: that a) nursing work has separate domains of labour, and b) that nursing work is not always caring for patients – it can also be in response to other types of demand, and c) nursing work reflects social expectations of nurses.

I found 5 ways researchers have talked about nursing work. At first, researchers had an integrated view of nursing work. Over time, different areas of nursing work were studied on their own, in order to learn more in detail (depth vs. breadth). In these types of individual narratives, there are 4 different kinds of labour: physical labour, emotional labour, cognitive labour, and organisational labour. One of the challenges is that as nursing labour was sub divided for research, we lost a picture of the whole. I think it is time to bring these types of labour back together, to give us a clear way of explaining nursing work.

My model of nursing labour:

Separating out different types of labour can help us by giving us terminology to explain how nurses add value to healthcare settings. It also provides terms that connect nurses across different areas and domains of practice. However, it is important to know that this is a framework for understanding- real life isn’t clearly divided into categories. Each type of labour has its own body of research, which I will describe in more detail below.

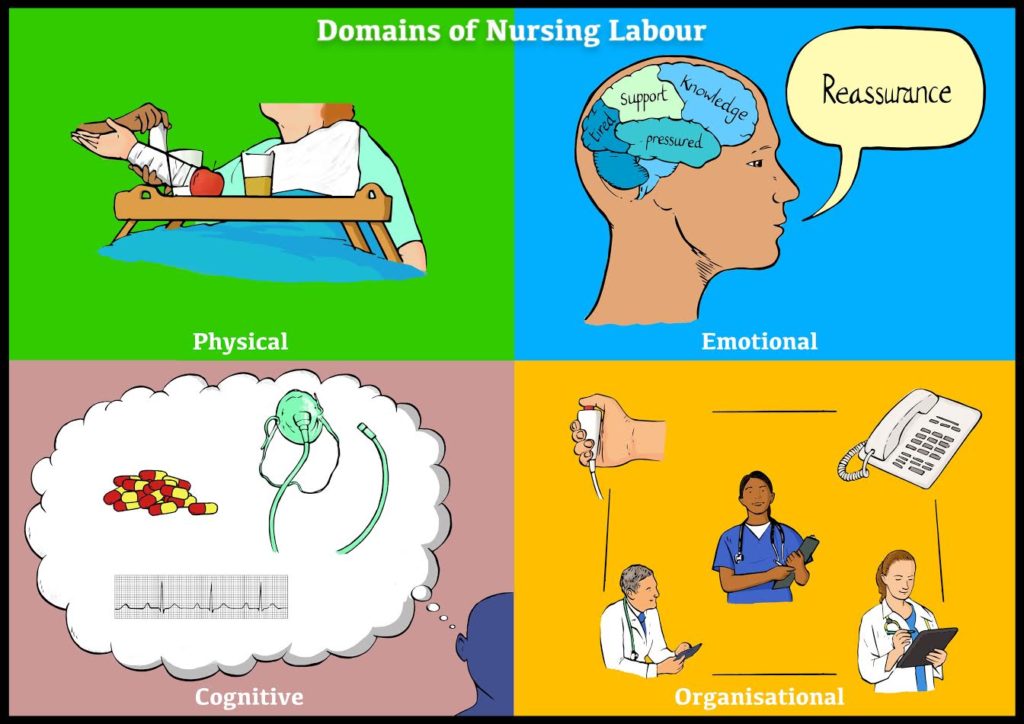

Physical labour

Physical labour is the ‘oldest’ type of labour, and most widely studied. It is also one of the easiest to track and see, so it is easier to study. Early on in nursing, physical labour was divided into basic and technical labour. What was meant by this was that basic labour was things every patient needed, like bathing and feeding. Technical labour referred to things that were specific to a patient because of his or her illness, such as managing a catheter or chest tube. The terms weren’t meant to say one was easier or harder; it was to demonstrate that some care requirements are universal, while others vary by patient. However, these terms were used to separate work, and things in the ‘basic’ category were seen as unimportant or easy. These terms have caused problems in nursing for years. To this day, things that are required by all patients are often delegated, or seen as ‘not nursing work’, despite the fact that they require a huge amount of skill (try feeding someone …it’s tough!).

This type of labour is talked about a lot because it is something that can be finished, or checked off the to do list. It is often a way of sorting activities too, especially in delegation. It is important to remember that just because physical labour is commonplace doesn’t mean it is easy or unskilled. In fact, there is a mountain of literature about how dangerous physical labour can be (back injuries!).

To learn more about physical labour in nursing, see the work of Jocalyn Lawler, Jan Savage, and Pam Shakespeare.

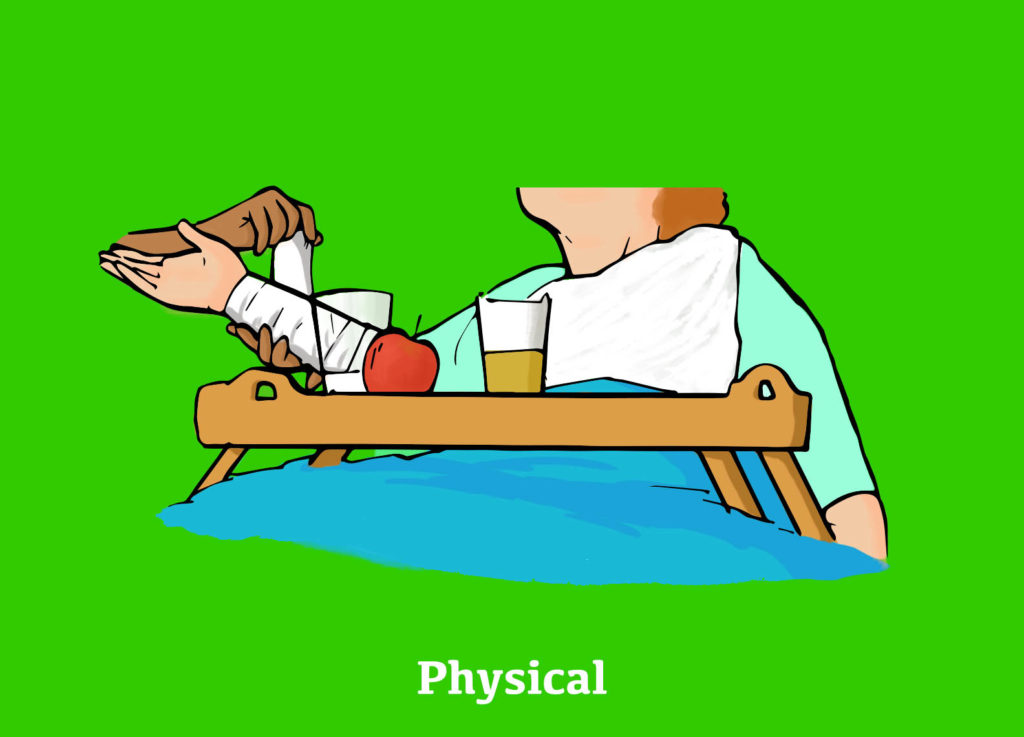

Emotional labour

Emotional labour is one of the main associations with nursing. The caring and compassion narrative is a favourite one for nursing organisations, who emphasise that nursing is the caring role in healthcare. Emotional labour is one way caring manifests, but it’s not the only one. Emotional labour can be understood as regulating your own emotions (and being paid for this) in order to create a type of environment that is desirable by the client or patient. Emotional labour research began with flight attendants, and how they were told to smile to put customers at ease. In nursing, a classic example is when a patient is doing poorly, and you are freaking out, but you maintain a clam demeanour so you don’t scare the patient. Another would be when you are upset by a patient’s death, but you remain stoic to support the family.

Nurses do emotional labour all. the. time. but it isn’t recognised. In part, I think this is because it is hard to see or measure, so it is hard to count as part of workload measurement (this is where managerialisation of healthcare comes into play). You can have two patients with the same medical diagnoses, but there can be wide variation in the amount of emotional labour they require. Because it’s hard to count, it’s often not taken into consideration when dividing up work. This can lead to nurses being overwhelmed by emotional labour, and lead to things like burnout, compassion fatigue, moral distress, and more.

To learn more about emotional labour in nursing, see the work of Arlie Hochschild, Pam Smith, and Catherine Theodosius.

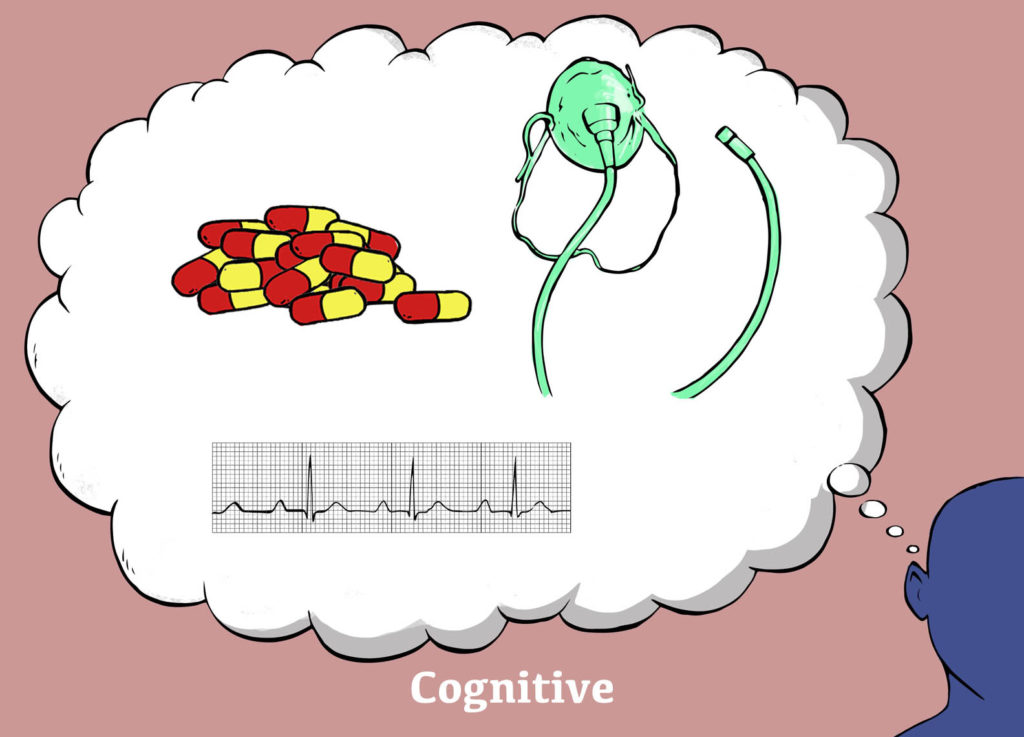

Cognitive labour

Cognitive labour is very unappreciated outside of nursing. Nurses know how much mental effort and critical thinking goes into planning care, but we are not very good at explaining this to others. In turn, people may assume it’s not happening. Like emotional labour, you can’t see or count it, so it can be harder to research.

There are two main ways researchers have understood cognitive labour: critical thinking and cognitive stacking. Critical thinking has been widely talked about in nursing (and some argue, to the point where the term is meaningless). Critical thinking is generally about knowing what the right thing is to do for a patient, given their context. However, it is challenging because context is influenced by social and emotional factors, so the ‘right thing’ for the patient may not be possible. This is where there is overlap between emotional and cognitive labour. There is lots of research about decision making, learning, critical appraisal and more. Almost all of this is done at an individual level, and looks at how to help nurses develop their thinking.

Cognitive stacking is a different perspective on cognitive labour (and I’d hazard to say, a more useful one). Cognitive stacking refers to keeping a number of things active in your mind at the same time. For example, Patient A needs something for pain, I need to see Dr B about Patient C, the family for Patient D is coming and I need to help him get to the commode beforehand… This mental list is held in nurses’ minds, and is constantly reviewed and re-prioritised. This may be helped by The Sheet that nurses keep in their pockets with a bunch of unreadable notes on it- this is a “cognitive artefact” that supports stacking. These ideas are really important because they open the door to a conversation about cognitive labour at a wider level. What happens when nurses are supposed to keep 18 things cognitively stacked? How many is unsafe? How much mental work are we requiring from nurses, and what are the consequences of this?

To learn more about cognitive labour in nursing, see Patricia Benner, and Patricia Potter.

Organisational labour

Organisational labour is the invisible labour in nursing. Nurses enact organisational labour all day, every day, but may not even know they are doing it. I didn’t know I was doing it until I read a book about it by Davina Allen and it changed my life. I finally had a way to explain the hard work that nurses do, that no one sees or values.

Organisational labour is work that creates a patient’s trajectory through a healthcare system, and sustains the system itself. Organisational labour can be both things that are needed for patients, like booking a porter to take them to an appointment, and things that keep the system working, like ordering more blankets for a ward. Ordering blankets may not seem like a skilled task, but it keeps everything going. And, if a patient doesn’t have a blanket, and is having a hard time regulating their temperature, you can have a real problem. Nurses don’t think that organisational labour is exceptional, because it is commonplace. However, I would argue it is just as skilled, and as essential, as any other kind of labour.

One example of organisational labour is documentation or charting. Nurses often groan (my previous self included) about having to document, seeing it as not being real work. However, documentation helps move a patient through the system. It provides a record of the delivery of expert care. It facilitates communication between teams. It arranges transitions, like discharge. Documentation is essential, and it is a skilled activity. I challenge nurses to start owning this as part of their practice, and not diminish its significance. Nurses in management do a huge amount of organisational labour, which is difficult and skilled. When I worked in management, I often heard “Do you miss real nursing?” I was still doing real nursing; the emphasis had shifted from physical to organisational labour, and everyone thought my role had ended. This shows what credit people give to organisational labour, which is a problem for anything that we spend 30% of our time doing.

As an aside, I think that I was unprepared for clinical practice as a new nurse because I didn’t know about organisational labour. In clinical placements, I only ever had one patient, so the amount of coordinating that was needed was limited. I got to independent practice and got slammed with 4 patients’ worth of phone calls and appointments and doctors to chase. I struggled because I had no idea how to manage. Nurses spend about 30% of their time doing organisational labour, and we need to make this visible for students as a skill they need to learn.

For further reading, the seminal author on organisational labour is Davina Allen. READ HER BOOK.

There are three main findings from this meta-narrative review: that a) nursing work has separate domains of labour, and b) that nursing work is not always caring for patients – it can also be in response to other types of demand, and c) nursing work reflects social expectations.

I hope that by considering these views, we can look at how nursing has changed, and drive this change in the future.